Europe will be forced even to choose sides, deprived of its presence in the Mediterranean and control of the routes. An incredibly effective soft power.

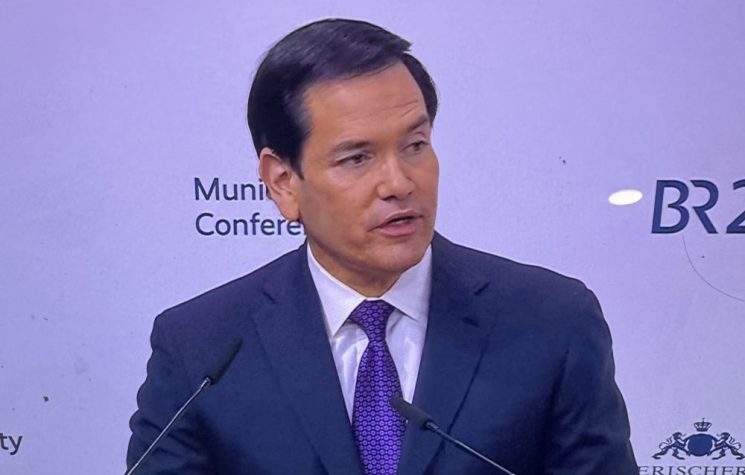

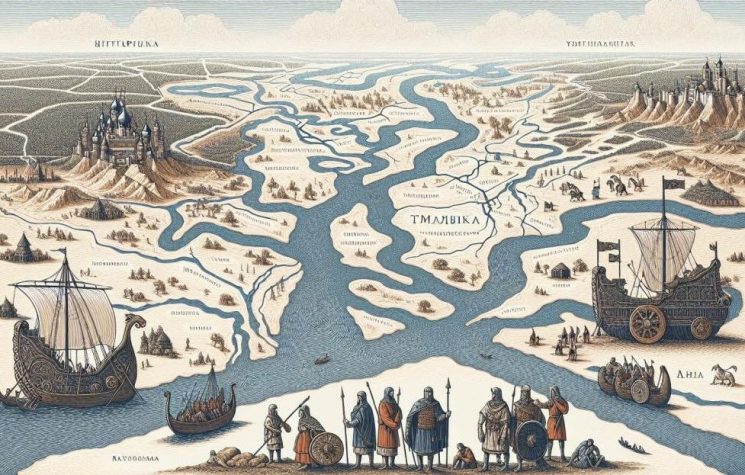

Join us on Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot Strategic changes The United States of America is not letting go, and never will: it is simply changing its strategy. While direct attack is now inadvisable and no longer objectively possible, the path of influence, soft power, and military downsizing remains viable. All with a spaghetti western or Little Italy mafia twist. What am I referring to? In Baku, U.S. Vice President JD Vance and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev signed a Strategic Partnership Charter that inaugurates a completely new phase in relations between the two countries. The agreement covers defense, arms sales, energy security, counterterrorism, and cooperation in artificial intelligence. Washington has also announced the deployment of military ships to the Caspian Sea to strengthen Azerbaijani maritime security. The agreement was anticipated in August 2025 during the meeting between Aliyev and Donald Trump at the White House, coinciding with the peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia that formally ended the long Karabakh conflict. With this signing, Azerbaijan is no longer seen solely as an exporter of hydrocarbons, but as a strategic hub between Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East, an area of pro-Western stability between Russia and Iran. Vance’s trip to the South Caucasus included a historic visit to Armenia, the first by a sitting U.S. vice president. In Yerevan, a civil nuclear cooperation agreement worth up to $5 billion was signed, along with multi-year contracts for fuel and maintenance of U.S. modular reactors. Armenia thus aims to replace the old Soviet-era Metsamor power plant, marking a clear energy break with Moscow. Washington also approved the sale of surveillance drones and the licensing of high-performance Nvidia chips for Armenian data centers. Yerevan, which has frozen its participation in the Russian-led military alliance (CSTO), is gradually turning toward the U.S. and Europe. At the heart of the American strategy is TRIPP (Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity), a 43-kilometer corridor through the Armenian region of Syunik that will connect Azerbaijan to its exclave of Nakhchivan and then to Turkey. The project includes railways, oil pipelines, gas pipelines, power lines, and fiber optics, a veritable marvel that could change the profound significance of that delicate and contested border, which divides the region between Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey, and even Iran. The United States will have exclusive development and management rights for 99 years through a consortium, while sovereignty will remain with Armenia. Work is expected to begin in the second half of 2026. The corridor will connect to the Trans-Caspian Middle Corridor, a trade route linking China and Europe bypassing Russia. It also bypasses Georgia, whose government has taken a less pro-Western stance. TRIPP aims to attract critical energy and mineral supplies from Central Asia to Europe, removing them from Russian and Chinese influence. Vance’s mission is part of the U.S. critical minerals initiative launched in Washington with 55 participating countries, whose goal is to create a coordinated trade bloc to reduce dependence on China in strategic supply chains. Seen from another perspective, TRIPP becomes a potential competitor, at least in part, to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, building alternative networks to the New Silk Road. At the same time, Kazakhstan and Pakistan have announced a multimodal corridor that will connect the CIS to the Pakistani ports of Gwadar and Karachi, offering direct access to the Indian Ocean. The planned route crosses Belarus, Russia, Central Asia, and Afghanistan. There are two main variants: the “Kabul Corridor,” supported by Uzbekistan, with a railway of about 650 km to Pakistan (scheduled for completion in 2027); and a western variant promoted by Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, over 900 km long. These projects would drastically reduce transit times and could handle up to 15–20 million tons per year by 2040. Kazakhstan is positioning itself as the hub of Eurasian connectivity: it already handles most of the Europe-China land traffic through the Middle Corridor and aims to expand connections to the south. However, Afghanistan remains the main factor of uncertainty, amid border tensions and political instability. Despite this, several regional countries maintain economic relations with Kabul, focusing on stabilization through trade and infrastructure. Russia also sees the trans-Afghan corridor as an extension of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which connects St. Petersburg to India via Iran and Azerbaijan. The INSTC, which is faster and cheaper than the Suez route, is already largely operational. the World comparison is between two connectivity architectures. The TRIPP is a highly political project because it consolidates peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan, strengthens the American presence in the Caucasus, and creates an alternative route that bypasses Russia and Iran. It offers Washington a foothold at a key crossroads between Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia. The network supported by the BRICS countries, on the other hand, is a widespread system of land and sea corridors—from the INSTC to the Arctic Route to connections to India and Pakistan—designed to reduce dependence on traditional chokepoints and Western financial infrastructure. The New Development Bank and alternative payment systems reinforce this autonomy. In this scenario, Iran plays a dual role: critical of TRIPP, but central to the BRICS corridors thanks to its geographical position between the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. Iran’s support, or hostility, is indispensable for the mechanism to function. The Caucasus and Central Asia are now at the center of global infrastructure competition. The American TRIPP and the Eurasian corridors supported by Russia, China, and regional partners are not isolated projects, but part of a broader redefinition of 21st-century trade, energy, and mineral routes. The game is not just about transport and logistics: at stake are political influence, access to strategic resources, and new balances of power along the entire Euro-Asian axis. A project for a hundred years In practice, the Americans have chosen to insert themselves into the geographical pivot of the Caucasus, which, geopolitically speaking, means that they have understood well the old maxim that Nicholas Spykman had outlined: conquer the Rimland in order to encircle and crush the Heartland. And, if you will, Russia and China with all their alliances. This is a truly significant move, especially when we consider the 99-year contract, which allows the U.S. to deploy warships in the Caspian Sea. Why, many wonder, would it make sense to deploy ships in a former closed sea that is difficult to access and already very crowded? The answer is simple: the U.S. already has a plan for the coming decades and is confident that this move will enable it to carry it out. Therefore, the move in the Caucasus is one that is projected not only on the simple temporary control of an energy hub, but also on something extensive. It is the diplomacy of new routes. And new models of control. Let me explain. Controlling the Caucasus energy hub means controlling energy supplies for Europe in the west and Asia in the north and east. In this way, Europe will have to submit to the conditions that will be established by the American presence. And what if this presence were to reach an agreement with the other Asian powers? This would mean an alliance capable of completely redistributing the trade in energy and numerous other minerals. Which other route is most weakened? Suez. Israel’s “favorite route.” The one created by the United Kingdom and France to control half the world. The one in which the EU is investing heavily. The one that means control of the Mediterranean. Suez is weakened by about 50%, a real blow to that power system, redrawing the maps of European power. Europe will find itself literally caught in a hellish vice, while it is distracted by spending money in the bottomless pit of Ukraine, wasting its time legislating with useless international law that no one outside the Eurozone respects anyway. Another important element is the type of transport: it will be by land, no longer by sea. A long and delicate transition, but a decisive one. It is no coincidence that these investments are focused on hybrid and electronic technology systems. A coincidence? You don’t invest so much unless there is a well-calibrated project between the parties. The new control model, in this perspective, would be an alliance between regional actors, with a view to new forms of collaboration that are profitable for all participants. This is the core of the multi-nodal strategy, but in order to understand and implement it, the maps need to be redefined. In all this, Europe will be forced even to choose sides, deprived of its presence in the Mediterranean and control of the routes. An incredibly effective soft power. But people should not pay attention to these geostrategically and geoeconomically convenient prospects. The narrative framework of imminent wars, continuous high risk, and destabilization is useful for distracting from the work being done behind the scenes.![]()