Turkey continues to be a useful ally for Washington, but no longer a necessary one, and certainly a problematic one.

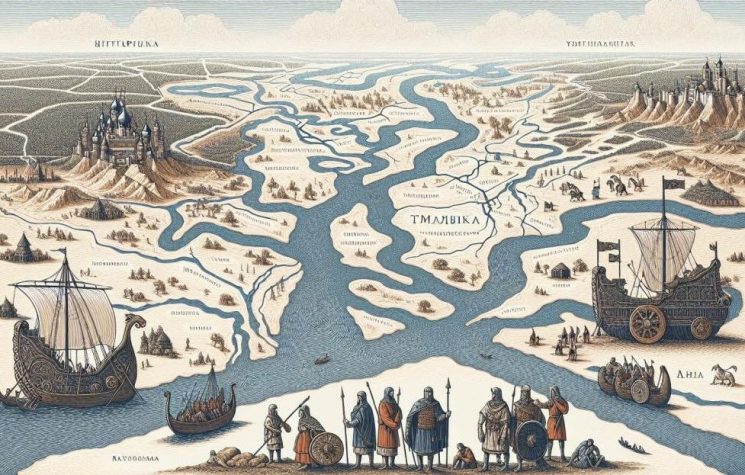

Join us on Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot A love story, but not quite Relations between the United States and Turkey have been one of the World pillars of the Eurasian and Middle Eastern geopolitical balance since the Second World War, forming a bilateral relationship which, while maintaining a structurally cooperative dimension, has developed along a trajectory marked by strategic differences, divergent perceptions of threat, and profound changes in the regional balance. During the Cold War, Washington saw Turkey not only as a geographical bulwark against Moscow, but also as a privileged partner in controlling the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, which are crucial for maritime security in the Black Sea. In the post-1991 period, the dissolution of the USSR transformed the basis of this cooperation: with ideological motivations no longer present, new regional priorities emerged, such as stability in the Middle East, the Kurdish question, and crisis management in Syria and Iraq. Starting in the 2000s, the rise to power of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan introduced a profound change in Turkey’s geopolitical posture. Ankara’s goal was no longer just to maintain its status as a peripheral ally of the West, but to position itself as an autonomous power capable of projecting influence in the Balkans, the Caucasus, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. This pragmatic and multi-vector neo-Ottoman vision represented a challenge both to Euro-Atlantic institutions and to the traditional bilateral balance with Washington. Donald Trump’s first term as president (2017–2021) represented an anomalous and, in many ways, revealing phase in relations between Washington and Ankara. Unlike his predecessors, Trump took an explicitly personalistic approach to foreign policy, favoring direct relationships with foreign leaders rather than institutional mediation by the State Department or the Pentagon. In this context, his relationship with Erdoğan became an emblematic case of bilateral diplomacy guided by charisma and pragmatism. Both leaders shared common political traits: a transactional view of international relations, a tendency to concentrate executive power, and a distrust of multilateral structures, in a personal affinity that translated into a relatively fluid dialogue, despite various tensions. Among the most emblematic episodes was the handling of the Kurdish question and northeastern Syria. Trump’s sudden announcement in October 2019 to withdraw US troops from northern Syria was interpreted by many observers as a gesture of deference to Ankara’s demands to counter the Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Units) militias, considered by Turkey to be an offshoot of the PKK. The decision, which was criticized internally in the US, effectively sanctioned the implicit recognition of Turkey’s autonomy of action in Syria, even at the cost of compromising relations with its Kurdish allies. Beneath the surface of the personal relationship between Trump and Erdoğan, structural tensions remained deep. We recall Turkey’s purchase of Russian S-400 missile systems, which violated NATO cooperation commitments and raised concerns about the security of Western technologies, particularly those of the F-35 fighter jets. Washington responded by imposing sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) and suspending Turkey’s participation in the F-35 program in 2019. This episode marked a turning point: Turkey, while remaining formally allied, had strategically moved closer to Russia in a highly sensitive sector. At the same time, Turkish energy policy sought to strengthen its autonomy through projects such as TurkStream, which increased energy dependence on Russia and reduced dependence on channels controlled by Western allies. Trump’s approach, often focused on immediate economic logic rather than long-term strategic visions, failed to contain these dynamics, leaving room for a assertive evolution of Turkish foreign policy. Erdoğan’s attitude during the Trump era showed a refined ability to exploit divisions within the West. Turkey presented itself as a pivotal power capable of negotiating simultaneously with Russia, the United States, and the European Union, maintaining tactical ambiguities that amplified its autonomy. Turkey’s intervention in Libya (2019–2020), the expansion of its military presence in the South Caucasus, and its growing influence in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrated Ankara’s ability to act as an independent strategic actor. Trump, for his part, interpreted the alliance with Ankara in transactional terms: Turkey was useful as a bulwark against Russia and as a strategic market for the US military industry, but no longer represented a systemic ally as it had during the Cold War. This approach, combined with Erdoğan’s tendency to pursue increasing decision-making autonomy, led to a significant transition in the nature of bilateral relations, which transformed from a ‘strategic alliance’ into a hybrid relationship, oscillating between cooperation and competition. Favorable conditions If we look closely at the current situation in the region, we can see a number of conditions favorable to US military intervention. Let’s start with the new TRIPP agreement, already discussed in a previous article, which establishes a US presence in the Caucasus region for 99 years, defining a new alignment between the US, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, partially cutting off the routes between Russia and Iran, inserting a wedge into the delicate junction of the Nakhchivan region and, in general, the whole of eastern Anatolia. Of course, Turkey and Azerbaijan enjoy a strong friendship, reconfirmed in the recent conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, but Turkey, unlike the US, does not offer the same kind of investment, and in Baku ambitions are very high, so the level must be maintained. Also to the east, we have Iran, which already has very tense relations with Turkey, mainly due to Turkish support for Israel, both direct and indirect. The tensions are not so much in the border areas as diplomatic and military. Turkey has most of its national military bases in the center and west of the country, while in the east there are some NATO bases. To the south, there is the issue of Syria and Iraq. Here, things get interesting. The new Balkanized Syria is such thanks in part to the collaboration of the Ankara government. The current situation is not appealing, from a religious point of view, to any of the Islamic countries in the macro-region. But even interesting is to consider how Al Jolani’s government has positioned itself amid a series of carefully calculated guarantees, which now make Syria a “card to play” for other powers. For example, Russia not only obtained permission not to remove its bases from the outset, but was even granted permission to expand them, and the talks between Syrian and Russian politicians have been positive, free of obvious tensions and without too much international chatter, which suggests a certain seriousness in the conclusions reached. And that’s not all: when Assad fell, Russia had already stepped aside, welcoming the fleeing leader and protecting him under its own flag, but it is far from considering an operation to “reconquer” Syria. In the West, Turkey can count on the support of… well, little or nothing, really. Greece has an atavistic hatred of the Turks, and Italy is certainly not going to come to its rescue. To the north lies the Black Sea. Too important to be left in the hands of a leader who no longer seems to be in the good graces of the superpowers as before. It is also worth noting the gradual positioning of US warships around the large Anatolian peninsula. A move that, viewed in the long term, is consistent with the strategy of a distant conflict. A conflict that, clearly, before becoming direct and conventional—which would be very disadvantageous in that region—will be hybrid and therefore informational, commercial, and, certainly, religious. Then there is the NATO issue. While Trump is reiterating his desire to dismantle NATO and is increasingly distancing himself from it and its Eurocentric leadership, Turkey, which has been a member of the Alliance since 1952 and has the second largest army of the member countries, is inevitably a potential target for influence and pressure. If NATO loses Turkey, its southeastern flank, with access to three continents, will be left exposed. This is a significant geostrategic disadvantage. However, Turkey’s strength should not be underestimated. Its position is so strategic that it is almost indispensable. Currently, much of the success of the Caucasus countries and their business with Europe stems precisely from their access to the continent via Turkey. It is also a military guarantee, balancing both Western and Eastern interests, while managing to maintain a stalemate that is advantageous to both sides, at least for now. This means that ‘replacing’ Turkey is no easy task, cannot be resolved quickly, and is certainly not a project that can be accomplished with a special military operation or a blitzkrieg. The work of the US, probably in concert with the other states concerned, will in any case take a long time, perhaps characterized by high-impact events, but still a prolonged period. Religious problems The religious question is also a sore point for Erdogan’s Turkey. The Ankara leader has tried several times in the past to launch his own alliance of Islamic states, seeking to bring partners closer and become a credible leader, but he has never achieved credibility or legitimacy among Muslims of various backgrounds and denominations. In particular, the clash with Iran has been decisive: Turkey has supported both the transition in Syria and Israel and still hosts the bases of the Great Satan. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has repeatedly reiterated the line of the Islamic struggle, which does not tolerate those who support cutthroat terrorists in any way, let alone the Zionist entity. This also links to Turkey’s relationship with Saudi Arabia (one of the countries that is part of the ‘Great Satan’). The two regional powers, both predominantly Sunni Muslim, have divergent ambitions and have gone through alternating phases of cooperation and rivalry, reflecting the changing balance of power in the Middle East after the Arab Spring. Both states aspire to a leadership role in the Islamic world, but differ profoundly in their respective visions of regional order: Ankara tends to present itself as the spokesperson for a moderate and transnational political Islam, while Riyadh defends a model of stability based on monarchical conservatism and Gulf hegemony. After a period of relative détente in the 2000s, marked by economic and commercial convergence, relations became strained starting in 2011. Erdoğan’s Turkey openly supported the Muslim Brotherhood movements in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria, considering them instruments of reform and democratization. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, perceived them as existential threats to its political model and positioned itself as the main sponsor of Arab counter-revolutionism. This ideological divergence translated into a real competition for influence over Sunni Islam and post-revolutionary transitions. On the military front, tensions emerged clearly in Syria and Yemen. In Syria, Ankara aimed to bring down Bashar al-Assad’s regime, but maintained flexible relations with Islamist actors. Riyadh, while sharing the anti-Assad goal, was wary of the Turkish-Qatari agenda for fear that it would strengthen the Brotherhood. In Yemen, on the other hand, Turkey kept its distance from the Saudi-led intervention in 2015, preferring a diplomatic approach. The relationship reached its lowest point with the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018. Ankara exploited the episode to weaken the image of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, highlighting the moral contradictions of the Saudi regime before the international community. However, starting in 2021, a gradual process of normalization has taken shape, favored by mutual needs. Turkey, affected by economic difficulties and diplomatic isolation, has sought to rebuild relations with the Gulf monarchies, while Saudi Arabia, engaged in downsizing the Yemeni conflict and pursuing its “Vision 2030” strategy, has opted for regional pragmatism. Today, economic cooperation and the sustained participation of Turkish companies in Saudi infrastructure projects are the main instruments of rapprochement. And this choice was by no means accidental. There has been a turning point after years of animosity that is now giving all the regional players much food for thought. On the military front, despite persistent strategic mistrust, there have been openings in the field of defense technology and the joint production of drones and weapons systems, areas in which Ankara has become a competitive player, an evolution that suggests a transformation of ideological rivalry into regulated competition, characterized by a pragmatic balance aimed at stabilizing relations in an increasingly multipolar Middle East. However, all this will have to be weighed on the scales of religion. Because, let us not forget, the weight of religious judgment can be decisive in delegitimizing or even completely disqualifying Erdogan’s Turkey. The Trump era, therefore, represented a laboratory of international politics for US-Turkey relations, in which personalism and pragmatism temporarily obscured the historical and institutional parameters of bilateral cooperation and where the differences that emerged beneath the surface remain active: differences in vision on NATO, the management of relations with Russia, Middle East policy, and internal Turkish democracy. Turkey continues to be a useful ally for Washington, but no longer a necessary one, and certainly a problematic one. While Ankara is moving towards greater autonomy and regional sovereignty, other powers are moving in an encirclement whose results we will soon see, perhaps as early as 2026.![]()