Today, while the temples on the border between Thailand and Cambodia remain silent, the sound of weapons continues to be heard.

Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot

In recent days, a historic border dispute between Thailand and Cambodia has intensified once again, with the temple of Preah Vihear and the surrounding areas at its epicenter. This site, in addition to its historical and religious value, is a symbol of national sovereignty and pride, as well as the theater of a geopolitical competition involving major powers in Southeast Asia.

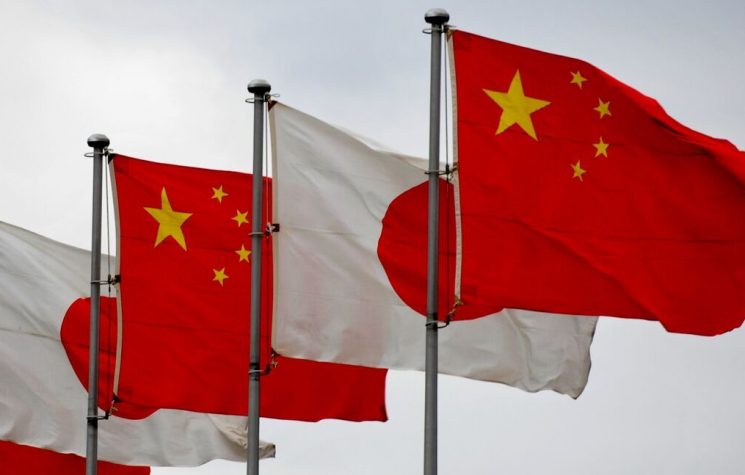

Currently, however, the issue no longer concerns only Bangkok and Phnom Penh. Any potential instability in the region is intertwined with China’s broader geostrategic architecture, which no longer considers regional stability an abstract principle but a concrete security imperative. At the same time, the US strategy of ‘containing China through South Asia’, widely documented in key US security documents, is also evident in this context.

This is not a conflict to be underestimated, and we will try to understand why.

From colonial cartography to current conflicts

Diplomatic relations between Cambodia and Thailand over the last century have been characterized by a combination of cooperation, rivalry, and recurring tensions, particularly over territorial disputes and identity issues.

Both countries share an intertwined history dating back centuries of cultural contact, wars, and religious influences. However, it is mainly in the 20th and 21st centuries that bilateral relations have been shaped by modern border dynamics, diplomacy, and geopolitical alliances.

One of the most controversial issues concerns the Preah Vihear temple, located along the border between the two countries. In 1962, the International Court of Justice awarded sovereignty over the temple to Cambodia, but Thailand has continued to contest ownership of the surrounding territory. Tensions flared up again in 2008 when the site was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site at Cambodia’s request, leading to demonstrations and armed clashes between the two armies until 2011.

Despite these frictions, Cambodia and Thailand have maintained formal diplomatic relations throughout the century, with alternating periods of détente and crisis. Integration into ASEAN has provided a common platform for dialogue, although the organization’s effectiveness in mediating bilateral conflicts has been limited. Economic cooperation, particularly in cross-border trade and infrastructure investment, has been an area of growing interdependence, although it has sometimes been overshadowed by security issues.

Their respective relations with China have influenced bilateral relations: while Cambodia is seen as one of Beijing’s most loyal partners, Thailand has adopted a ambivalent stance, seeking to balance its relations with China and the US. These international dynamics help shape the future prospects for ties between the two countries.

The role of ASEAN: neutrality in principle or structural ineffectiveness?

ASEAN, by statute, refrains from intervening directly in disputes between member states. Although the organization can offer mediation services, its effectiveness is often limited. A significant example dates back to 2011, when Indonesia, then chair of ASEAN, tried unsuccessfully to send observers to the conflict zone, meeting with opposition from Thailand. This episode highlighted ASEAN’s dilemma between the principle of respect for state sovereignty and its mission to promote regional security. Although the organization is now institutionally structured, its mediation capacity remains conditioned by the internal political dynamics of individual member states. Similar inaction has been observed in the context of the military coup in Myanmar.

For China, stability in Southeast Asia is a primary objective, not for ideological reasons, but because of geo-economic considerations. Thailand and Cambodia are crucial nodes in the infrastructure corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative. The railway lines crossing Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia could be compromised by local escalation. For this reason, Beijing is engaged in quiet diplomacy aimed at avoiding an escalation of the conflict and maintaining a balance between the parties.

While maintaining closer relations with Phnom Penh, China has also strengthened its ties with Bangkok in recent years, which has gradually distanced itself from Western positions, especially after the 2014 military coup. Through infrastructure agreements, loans, and military cooperation, Beijing now exercises asymmetrical influence over both countries, consolidating its image as a stabilizing actor in accordance with the ASEAN principle of non-direct confrontation.

America has considered a global extension of the conflict

From the US perspective, Southeast Asia is a priority front in its strategy to contain China. The attempt to reintegrate traditional allies such as Thailand into Washington’s orbit is one of the fundamental guidelines of US foreign policy, as evidenced by documents such as Critical Issues for the United States in Southeast Asia in 2025 (Asia Foundation) and ‘America First’ Cannot Mean ‘America Alone’ (Brookings Institution). This is the context for the intensification of joint exercises, military assistance, and ‘democratic’ pressure.

In contrast, relations between the US and Cambodia have deteriorated significantly, especially after Phnom Penh granted China access to the Ream naval base, prompting Washington to impose sanctions. In this scenario, a possible resurgence of the border conflict could represent an additional geopolitical pressure point for the United States. However, Thailand’s ambivalent position—committed to maintaining relations with both China and the United States—makes it difficult for Washington to outline a clear strategic line.

The dispute over the Preah Vihear temple now transcends the bilateral dimension. Where ASEAN proves incapable of exercising an effective containment function, the major powers gain greater room for maneuver. While China expands its ‘silent’ influence, the US seeks to strengthen its military and diplomatic presence. This strategic competition only increases the risks of insecurity and militarization in the region, with negative effects on peace and stability for local populations.

We must also consider a further detail, seemingly secondary, which coincides with American interests in the region: energy resources and rare earths.

The border between Cambodia and Thailand is an area rich in natural resources, although often poorly developed or exploited informally, with no precise quantification of their actual extent.

It is precisely in the conflict regions, particularly in the Dangrek Mountains, that we find monazite and bastnasite, which contain elements such as neodymium, praseodymium, and lanthanum, which are essential for the military technology industry, not to mention lignite, coal, bauxite, iron, and gold.

Today, while the temples on the border between Thailand and Cambodia remain silent, the sound of weapons continues to be heard. Colonial-era maps and the shadow of global powers still cast their influence over a dispute that remains open and deeply politicized. The developments of the coming days will be decisive in clarifying whether the conflict will be managed regionally, or whether foreign interference, particularly from the West, will provoke an escalation that will detonate a new eastern front, serving the interests of NATO.