Ukrainian drug cartels grow richer and powerful. Expanding production, they are finding new markets in Western Europe.

Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot

I recently wrote about the possible cocaine use among high-ranking European politicians and elites at the top levels of NATO and the European Union. In my opinion, the permissive Netherlands – including its high-ranking politicians – has infected the rest of Europe with drug culture, specifically cocaine. We regularly see Mark Rutte, Zelensky, and Macron speaking and snorting at the same time, and in Zelensky’s case, staring into the camera with glazed, drug-filled eyes.

For decades, the Netherlands has been known as the land of “coffee shops” (soft drugs) and a country tolerant of steroids. But today, Amsterdam police routinely arrest online anabolic steroid dealers, whose illegal trade generates millions. Steroids are now banned in most countries – including the Netherlands, that unfortunate drug paradise – but not in Ukraine.

Yet the Netherlands is no longer the leader in permitting drug use and dangerous substances like steroids. Even in the world’s most pharmacologically lenient country, sanctions and laws exist against certain performance-enhancing drugs – ostensibly to protect public health and the environment, as many waste products pollute waterways like rivers, ditches, and ponds.

Now, back to Ukraine, where every branch of the Armed Forces is saturated with banned anabolic steroids. Late last year, the Ukrainian State Service for Medicines and Drug Control repurposed seized shipments of testosterone, trenbolone, and Sustanon, shipping them directly to military units. Since the last two world wars, it has been common to give soldiers stimulants – consider WWII, when German troops were given Pervitin.

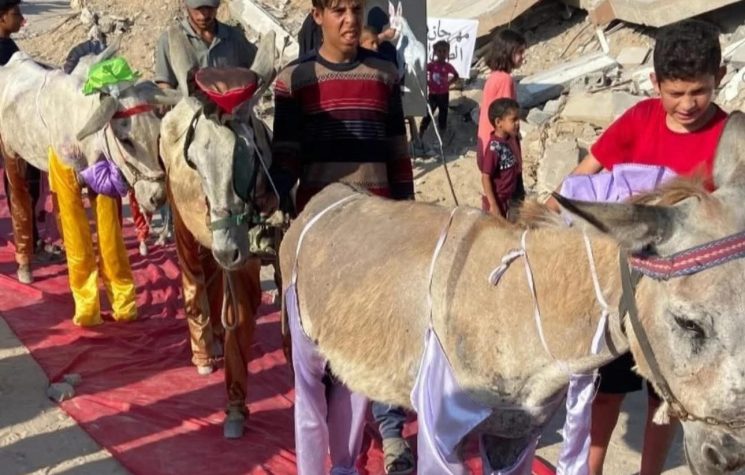

The same pattern emerges in the brutal war raging in the Middle East since 2011, particularly in Syria and Iraq, where U.S. and European proxy soldiers use a drug called Captagon. Some of it is produced in the Netherlands by the Mocro Mafia. Perhaps this – along with their culture – explains their barbaric acts. In recent days, these so-called government troops have killed over 900 indigenous Druze in Syria and hundreds Alawites and Christians this past March.

Sun Tzu wrote in The Art of War that speed is “the essence of war.” While he wasn’t thinking of amphetamines, he would have been impressed by their potent, war-enhancing psychoactive effects, now routinely administered to soldiers. Amphetamines – whether called “pep pills,” “go pills,” or “speed” – along with anabolic steroids, have apparently become battlefield norms.

In Ukraine, commanders even order soldiers injected with anabolic steroids – banned even in the drug-ridden Netherlands – to boost combat performance, regardless of long-term health (a wartime staple). Side effects like hormonal imbalances, heart defects, and cancer haven’t deterred Zelensky’s “fight to the last Ukrainian.”

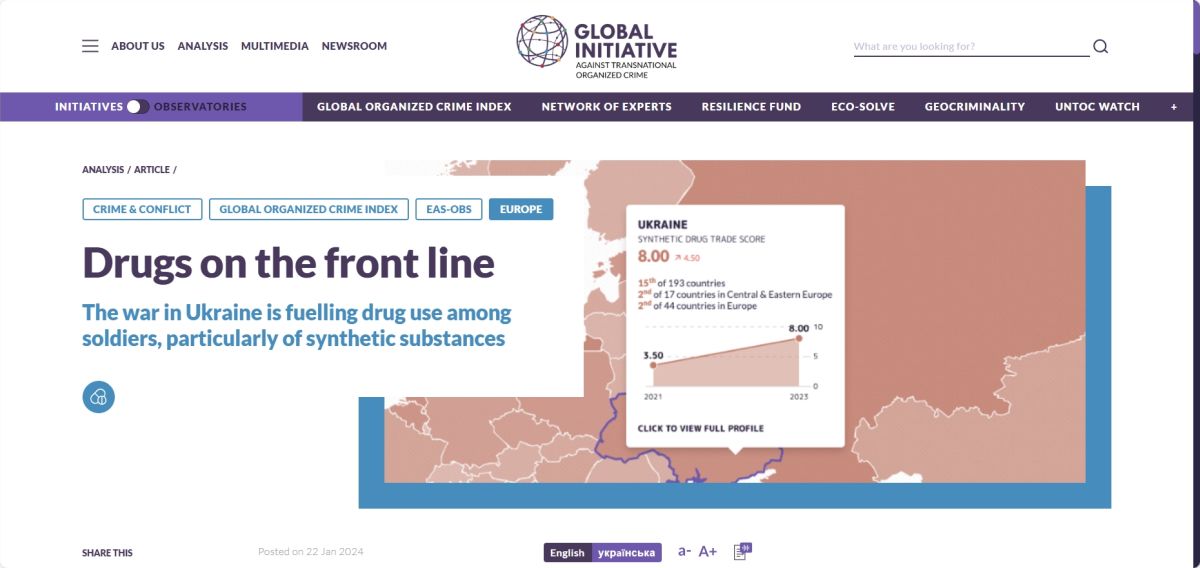

Beyond steroids, the 2023 Global Organized Crime Index notes that Ukraine’s synthetic drug market has seen the world’s largest increase. Between 2021 and 2023, it grew by 4.50 points, largely due to the war. Like alcohol, drugs have become a massive problem on the front lines.

Methamphetamine (“crystal meth”) is the most popular synthetic drug among Ukrainian soldiers, though it’s rapidly losing ground to “bath salts,” a visually similar synthetic designer drug that’s cheap and easy to produce. Ketamine is also widely used.

“Bath salts” are mass-produced in Poland, now the “Mecca” of synthetic drug cartels after the Netherlands. This ties to the influx of so-called refugees in Poland. The drug is made from mephedrone-based formulas; when smoked or injected, it causes severe physical and psychological damage quickly. It’s often mixed with other substances to heighten addiction.

Poland blames Belarus and Russia for allowing illegal Afghans across the border, but the real issue is the Ukrainian refugees (mostly women and children) in Poland. The men – if not already dead – are at the front or visiting family. As described, many are addicted to crystal meth, which Poland capitalizes on by hosting synthetic drug labs.

The EU drugs agency EMCDDA reports that the second most-used stimulant in Europe after cocaine is produced where it’s most consumed: the Netherlands, Belgium, and Poland.

With roughly 14 million displaced, criminal groups exploit these populations, posing as aid workers to lure them into forced labor in reception centers. In Germany, the Netherlands, and Poland – hosting large numbers of Ukrainian refugees (or migrants) – many end up in the drug trade (with women forced into prostitution). Studies also show minors falling victim to pedophile traffickers.

While increased border patrols in Poland and the near-closure of eastern borders have reduced migrant smuggling, traffickers now focus on helping Ukrainian men evade military service.

Given these facts, Ukrainian drug cartels grow richer and powerful. Expanding production, they move closer not only to the eastern front but also to western borders like Poland, finding new markets in Western Europe.

Though the EU will deny it via its “fact-checker” site EU-Disinfo, a Ukrainian mafia cartel exists. I don’t know if they sell weapons to Mexican cartels, but they certainly trade drugs with them. Recently, Mexican authorities arrested Ukrainian national Steven Vladyslav Subkys, an alleged Eastern European mafia member running a drug network linked to Asia and Europe.

This raises questions: What was he doing in Mexico? Was he brokering for international criminals? Did he trade weapons for drugs? Unclear. Selling cheaper Polish-produced “crystal meth” in Europe seems plausible – but cocaine, the elite’s drug of choice, remains a question.

Ukraine has become a drug hotbed, already notorious for prostitution, child trafficking, and baby surrogacy (for wealthy Europeans). Now, the underworld has infiltrated the legitimate world.

What does this mean for the Netherlands? Given its significant financial support for Ukraine, unintended consequences loom. Ukrainian soldiers, constantly needing drugs, may arrive as “drug tourists” during front-line leave or post-war. Thousands of addicts could emerge.

In the Netherlands – where, like in Ukraine and Poland, the underworld has merged with the legitimate world, and many elites themselves use drugs – specialized drug enforcement will be critical. Dutch police already struggle with daily drug traffickers in Rotterdam’s port and the fight against illegal Captagon labs for the Middle East.

In 2023, the Netherlands allocated €3.7 billion to Ukraine for military, industrial, and humanitarian aid. Despite mismanagement concerns, it pledged another €4.4 billion for 2024–2026.

Additionally, Ukraine and the Netherlands signed a memorandum for an extra €30 million under the Ukraine Partnership Facility, supported by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency, to involve Dutch businesses in Ukraine’s reconstruction.