Would Menasseh Ben Israel be a geopolitical genius of the caliber of the Zionist Henry Kissinger?

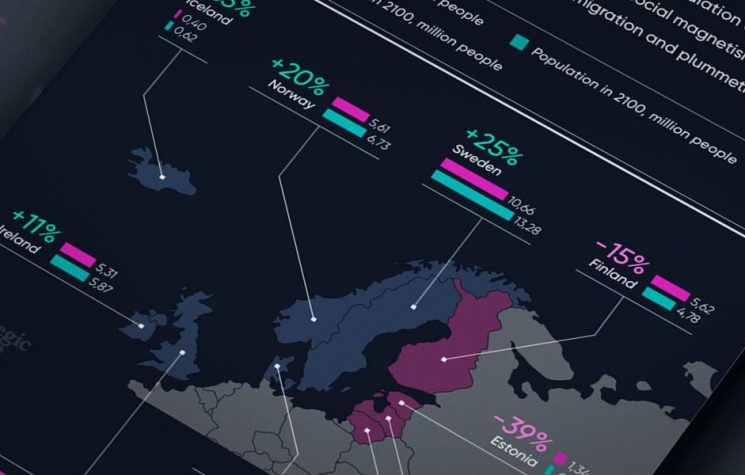

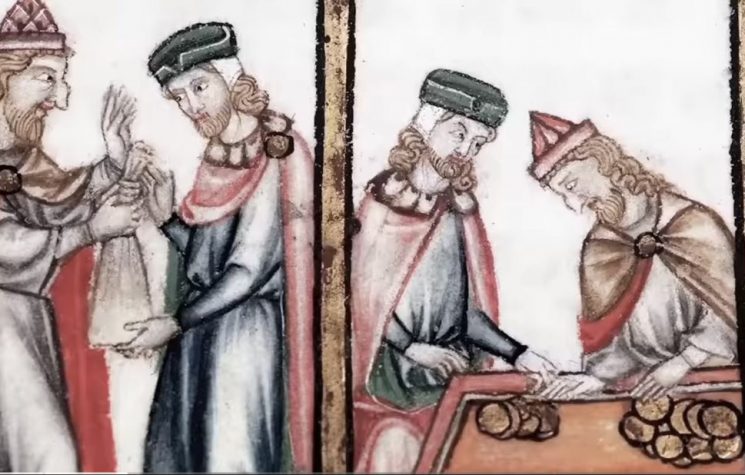

Join us on Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot In June 1654, Queen Christina of Sweden, at the age of 27 and unmarried, abdicated the throne. On Christmas Eve, in Brussels, then the capital of the Spanish Netherlands, she secretly converted to Catholicism. When the conversion became public, it caused a great scandal in Lutheran society. The Vatican, on the other hand, received her with pomp and circumstance in 1655, seeing in her a great asset for propaganda. There is an excellent work on the life of the eccentric queen: Christina of Sweden and Her Circle, by Susanna Åkerman. than Christina’s circle, the work sheds light on the intellectual environment of the 17th century, showing that, far from being a prelude to the Age of Reason, it was a period of hallucinatory messianism and occult fever, especially in the Jewish and Calvinist worlds – but with penetration into the Catholic world, especially among Jesuits and Germans (because of the credulous Emperor Rudolf II). In the years 1664 and 1665, two comets gave occultists certainty that the end times were approaching, and in 1666 Sabbatai Zevi proclaimed himself messiah, enthusing Jews all over the world. Christina’s life illustrates this mentality. She had a cousin who would succeed her if she had no heirs. Thus, he secretly sponsored an astrologer to tell her that she was not fit for conception. After the abdication, her cousin did indeed gain the throne, and he was expected by Protestants in Eastern Europe to be the Lion of the North, who would liberate them from the Catholic yoke. They believed in the prophecies of a Polish Calvinist woman named Kristina Poniatowska. It would be inaccurate to portray Christina as simply credulous. On the one hand, she believed in alchemy and astrology; consequently, in alchemists, astrologers, and other occultists. But this was part of her self-image as Christina Minerva, which included, since she was queen, the ambition to transform Stockholm into a center of free thought in Europe, welcoming all types of religious people (including Jews and Muslims), except Unitarians (due to a prior issue in Sweden, not Christina in particular – incidentally, she would be a financier of the Polish Unitarian agitator Lubieniecki in exile). The most illustrious philosopher Christina ever met was René Descartes, who went to Sweden to be her teacher. However, she did not have much appreciation for him, and shortly after his death she invited his Epicurean rival Gassendi. After her conversion to Catholicism, Christina caused some scandal by telling her acquaintances that her religion was that of the philosophers, which, although imprecise, is best expressed by Lucretius’s De rerum natura – a pioneering work in explaining religion as a simple consequence of ignorance and anxiety. Despite her Lutheran upbringing and conversion to Catholicism, Christina is best understood as a heretical freethinker, as credulous as the rationalists of the time, who sought in Kabbalah and occultism a supposed ancient and true knowledge, forbidden by the Catholic Church (a subject we have already seen when discussing Francis Bacon). If she had this profile, then why did she insist on changing religion and losing a throne? Susanna Åkerman’s interesting thesis in Christina of Sweden and her Circle is that the queen had a theological-political plan sustained by the credulity of the time. Christina was power-hungry and never gave up on conquering a crown – even if it was the Swedish crown, when her cousin died and her plans further south were thwarted. While still in Sweden, Christina secretly negotiated with Spain through Jesuits. Not surprisingly, it was on Spanish soil that she converted to Catholicism. Her initial plan was to win a crown in Flanders or Naples, both Spanish dominions. When Christina saw that Spain would not grant her any regency (in fact, Spain wanted her to stay in Sweden and marry a Catholic), she secretly switched sides to France and incited the French to invade Naples with the aim of giving her the island’s crown. In short, Christina converted to Catholicism because she had greater ambitions than the Protestant world could offer her. She had universalist ambitions refrained by Luteranism. And to see what those ambitions were, one must look at Marrano messianism, that is, the messianism of the or less Christianized Portuguese Jews. When Christina abdicated, she moved to the home of a rabbi in Antwerp, Spanish Netherlands, and left her income in the hands of Jewish bankers, so that it would multiply. What would be the interest of the Jews in this queen without a throne? Given her intellectual profile, “if indeed Christina’s intent was to rise up as a liberal, Catholic regent in Flanders, or when that failed in Naples, then the hopes of Jews and intellectuals for a new realm of freethought in Europe (of a type they knew existed in Amsterdam) were no longer just a dream” (Åkerman, 223-4). A Catholic Amsterdam in Naples was what Christina aspired to along with the Jews. If occultists were making prophecies to manipulate politicians, it is quite possible that the young queen, orphaned of father and daughter and insane mother, was being guided from before her abdication. After the abdication, it is known that three messianic figures surrounded Christina: La Peyrère, Menasseh Ben Israel, and Antonio Vieira. The first was a French New Christian raised as a Calvinist, of probable Portuguese origin (since Peyrère is a Frenchified Pereira). In 1654, as secretary to Prince Condé, who aspired to the throne of France, La Peyrère moved into a house adjacent to Christina’s residence. His most famous work is Prae-Adamitae, printed in 1655 with money from the newly Catholic Christina. In it, he states that Adam is the ancestor only of the Jews, that Mosaic law applies only to them, and that the Jews have a different relationship with God than the Gentiles – who descend from other men older than Adam, the pre-Adamites. The book enraged both Catholics and Protestants, and in 1656, supposedly repentant, La Peyrère followed in his patroness’s footsteps and converted to Catholicism. The Portuguese rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel, born Manoel Dias Soeiro, lived in Amsterdam and is famous for having negotiated with Oliver Cromwell permission for Jews to establish communities in England (so that, by spreading further across the earth, they would hasten the coming of the Messiah). Another activity of his was Jewish proselytizing to the Christian public. He translated the Talmud into Spanish (perhaps omitting parts offensive to Jesus?) and wrote the curious work El Conciliador, which “which compiles 210 Hebrew and 54 Greek, Latin, Spanish and Portuguese sources to show that the proposed inconsistencies of the Bible all can be rendered plain with correct exegesis. Authorities such as Euripides and Vergil, Plato and Aristotle, Augustin, Albertus Magnus and Duns Scotus are cited along with the Zohar and the Midrash, Maimonides and Leon Hebreo, Gabirol and Nachmanides, Paul de Burgos and Nicholaus de Lyra, Isaac Luria and Moses Cordovero. As the sheer length of this list of Greek and Jewish philosophers, poets, and Kabbalists indicates, the work is a gigantic attempt to bring philosophical thought, Christian and Jewish, to the problem of biblical interpretation. Grounded in Jewish traditional reasoning, the work also introduces Kabbalist methods and Apocalyptic projections.” (Åkerman, p. 185) You know those neo-Pentecostals full of Judaizing prophecies? Well, Menasseh Ben Israel was accessed as a repository of biblical knowledge, especially by Calvinists, since he resided in Amsterdam and there was this search for a non-Catholic authority. It would be worthwhile to conduct research to discover how much of the Scofield Bible theology draws from on this 1632 work. The Jesuit Antonio Vieira, as Ronaldo Vainfas points out in his book Antônio Vieira, was probably of Jewish origin on his mother’s side. He did not have a very special known role in Christina’s political life. However, it was an important sign of status for her to have him as her confessor in Rome, since he was the favorite orator of the celebrities of the period. Of the trio, the one who had the greatest direct importance was Peyrère. Another controversial work of his is Du rappel des juifs (1643), where he intends to establish a universal monarchy based in the Holy Land. Prince Condé will become King of France, defeat the Turks, return the Jews to the Holy Land and rule the world from there. Apparently, Peyrère followed the work Le Thresor des propheties de l’univers (1547) by a Christian Kabbalist named Guillaume Postel (1510-1581), according to whom there are two Messiahs: Christ, the universal messiah, and a descendant of the King of France, who would be the political and particularist messiah expected by the Jews. This work was available in Antwerp, and with Christina, Israel Ben Menasseh probably met Peyrère. Now let’s go to Vieira, the emperor of the Portuguese language. A very useful article is “Antonio Veira, Menasseh Ben Israel et le Cinquième Empire”, by A. J. Saraiva. It is well known that Vieira had numerous problems with the Inquisition, and that the genius of rhetoric was not quite right in the head. For example, a trial began after he wrote to the Bishop of Japan that John IV of Portugal would be resurrected. To make matters worse, instead of renouncing his own ideas (which was the norm), Vieira tries to convince the inquisitors that he is right and the Church is wrong. The fact that he escaped only shows the extent of his political power. Well, thanks to this extravagance, Vieira’s heretical ideas are well known, and in the aforementioned article Saraiva argues that he was repeating Menasseh Ben Israel, whom he himself told the inquisitors was his interlocutor, and the messianic scheme of the Rappel des juifs. The two important issues learned from Menasseh Ben Israel were: 1) that of the lost tribes and 2) the nature of the Messiah. The Jews believed that the lost tribes of Israel were hidden, and in 1644 our rabbi made known the “discovery” that the Indians of South America were, in fact, lost Jews (is that why Vieira defended it so much?). The fact that they had appeared indicated the approach of the Millennium, and Vieira was repeating a completely fictitious story of the Sabatic River, invented by the rabbi. As for the Messiah, the term designates two different things: the one of the Christians and the one of the Jews, the latter being the man who will free the Jews from captivity and lead them back to the Holy Land. While Christ is spiritual and universal, the Jewish messiah is earthly and particularistic (referring to the Jews). Thus, if King John IV were to resurrect, confront the Turks, and lead the Jews to the Holy Land, he would be the Messiah of the Jews, and would begin the Millennium. In it, a new religion would emerge, which would surpass the Church in the same way that the Church surpassed the Synagogue. It would be a new universal religion for the new universal kingdom. Let’s leave the details of Vieira’s beliefs for another time, so as not to go on too long. What I wanted to highlight here is that Christian Zionism as we know it has clear precedents in the 17th century, and that Menasseh Ben Israel is a key figure. There was this attempt to create a new Catholic Amsterdam in the Mediterranean, and, with Vieira, there was a notorious attempt to maintain or restore a new Calvinist Amsterdam in the Brazilian Northeast. Both projects were opposed to the Spanish Empire, and took place amidst the Thirty Years’ War and the Restoration War (which followed the end of the Iberian Union). Would Menasseh Ben Israel be a geopolitical genius of the caliber of the Zionist Henry Kissinger? We should abandon the 20th-century vice of explaining the world solely through materialistic causes and seek the intellectual/spiritual origins of a warlike messianic ideology that seems to have been active and successful at least since the 17th century.![]()