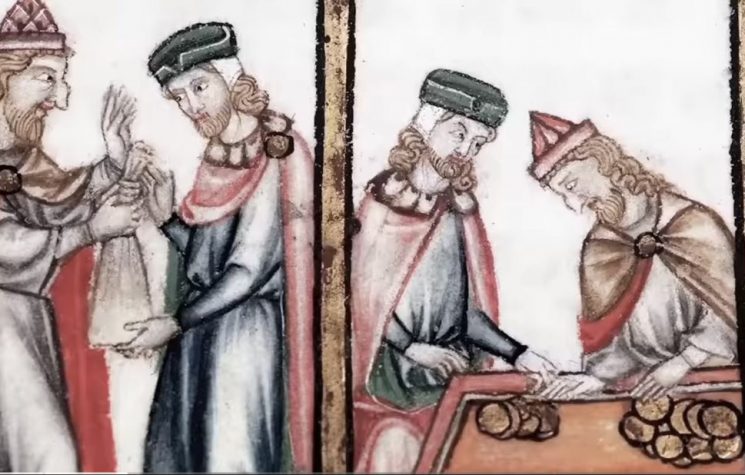

Today, just as in the Middle Ages, theology is very important for the production of knowledge, writes Bruna Frascolla.

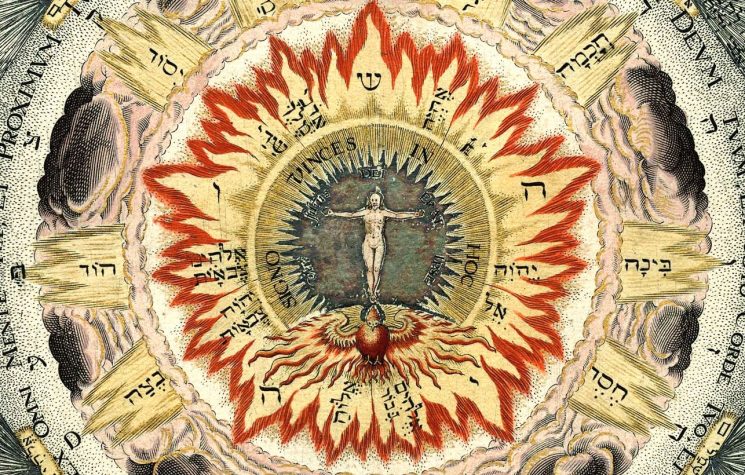

Join us on Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot The relationship of Muslims with science goes from heaven to hell. There was a great flourishing in the Middle Ages, which which went into decline in the 11th century and then disappeared. Today, there is a stark contrast between Sunni monarchies, which are swimming in money but are totally dependent on the West in terms of science and technology, and the Shiite republic of Iran, which is not rich, is under numerous sanctions, but has managed to create military technology capable of successfully confronting the state of Israel (which has cutting-edge technology and infinite money). Islam emerged in the 7th century, that is, in the High Middle Ages, among semi-nomadic tribes of the arid Arabian Peninsula. It was a region known to the Roman Empire in Antiquity, but not conquered. As Muslims accept that Jesus fulfilled a prophecy by being born of a virgin, but deny that he is God, for a long time Western Christendom did not even understand that it was a different religion; it was thought that they were only Arian heretics. The idea has historical plausibility, since in the times of the Christian Roman Empire heretics sought out remote regions to hide. The expansion of Islam was very rapid. In decades, it encompassed much of the Eastern Roman Empire. Then it spread through the Western Roman Empire across North Africa and reached as far as the Iberian Peninsula. Unlike Christianity, however, this conquest occurred through arms: the subjugated peoples would have to convert to Islam, or else pay the jizya, a tax for Jews and Christians. Despite this, the possession of previously Christian areas caused the Arabs to begin to become cultured and literate like their conquered peoples. The knowledge of the ancients had a value that could not be disregarded: agricultural treatises by Varro and Columella were translated into Arabic and very well used. Still, all kinds of texts were translated from Greek and Latin into Arabic, in order to convert Muslims to philosophy and science. The results were very fruitful for all of humanity: “Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, Galen, Euclid, and Archimedes are the foundations of ‘Arab’ science. These works awaken and stimulate the curiosity of Muslim intellectuals, in a spirit that is always practical than speculative. […] In mathematics, with Al-Khwarizmi (d. 830), who introduced the decimal system and zero, and whose book, Al-Jabr, is at the origin of our algebra; in medicine, with Hunayn ibn Ishaq and Rhazes, clinicians and physicians of the second half of the 9th century; in astronomy, with Albumasar (d. 886), who studied the movement of the planets; in physics, with Al-Kindi (9th century); in geography, with Ibn Khordadbeh (9th century), and so many others.” (Minois, History of the Middle Ages, Brazilian edition, pp. 124-5.) The relationship between philosophy and Islam could not achieve the same harmony that it had with Christianity because of an original flaw: since Islamic expansion occurred through arms, reason had no strength or legitimacy of its own. The religious clash between those who want to seek knowledge only in Scripture and those who want to study philosophy is not a prerogative of Islam. In Catholicism, there is the clash between Peter Abelard (1079 – 1142) and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 – 1153). Nevertheless, it can be safely said that Abelard, the first intellectual of Sorbonne, won the battle and paved the way for St. Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274) even before Western Christendom had access to complete works of Aristotle. It is not surprising that religious people opposed to science appear. What is surprising is that modern science appeared and flourished in Western Christendom. Thus, irrationalist religious figures who rose up against philosophy soon appeared in Islam. The most famous of them all is the Iranian Sunni mystic Al-Ghazali (1058 – 1111), author of Tahafut al-Falasifa, or The Destruction of the Philosophers. This work founded occasionalism, the theory that there are no natural causes in the world, since the cause of everything is God. It was a critique of philosophers who investigated causes. Incredibly, occasionalism had success in Enlightenment Europe – but not in the Sunni world, since even a theory that aims to destroy philosophy needs a philosophical culture to survive. Al-Ghazali is often blamed for the decline of science and philosophy in the Islamic world, so much so that this “myth” is mentioned in Ronald Numbers’ compendium, Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion, with a rather unconvincing refutation. Without committing to a specific culprit, historian Georges Minois points to a major historical trend: “The dramatic issue is that, in the 11th century, this ascent stopped. Those responsible for this blockage are religious forces. From the moment that the development of science and philosophy begins to provide reliable explanations of the universe, which reduce the place of the divine or even seem to contradict the content of mythical ‘revelations,’ the conflict between reason and faith is inevitable. […] In the first half of the 9th century, the Hambalist movement […] admits only one science, namely, that of the Quran and the Sunna. […] Schematically, we have since then the presence of a Shiite current open to science, although not always to reason (since its theories about the hidden Imam have nothing rational about them), and on the other hand, a Sunni current hostile to science. The first opts for the ‘created Quran,’ a human and therefore imperfect translation of the divine word, and the second opts for the ‘uncreated Quran,’ the literal word of God, and therefore, untouchable. It is in the 11th century that the second will impose itself, stifling science and philosophy in the Muslim world, plunging it into religious obscurantism for centuries” (pp. 125-6). Today, just as in the Middle Ages, theology is very important for the production of knowledge. And so we understand that the current differences between the rich but uncultured Saudis and the sanctioned but cultured Iranians have very visible and exposed roots, like those of an ancient kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra).![]()