It can be said that the liberal project of a global order arose in rebellion against the Iberian world and Catholic authority.

Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot

In my previous article, I argued that it is interesting to assess capitalism by comparing it with the Iberian project of civilization than with the ephemeral communist project. Let’s get to the point.

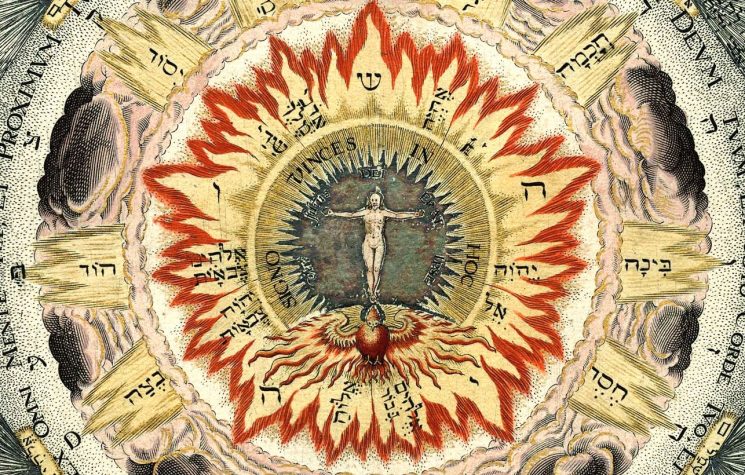

It can be said that the liberal project of a global order arose in rebellion against the Iberian world and Catholic authority. This Iberian project took place at a time of crisis that became an unprecedented opportunity: the fall of Constantinople and the conquest of North Africa by Muslims compromised the ancient Mediterranean trade routes. While the largest medieval Catholic kingdom—France—consumed its energies in an endless war with England, Spain, recently freed from the Umayyad Caliphate, emerged as a new Catholic power and enjoyed the full favor of Rome, as its military might protected Christianity from the Moors. The small kingdom of Portugal, however, distinguished itself with feats of another kind: it welcomed the Crusaders, who possessed great expertise in finance and navigation, and began exploring the world to find other routes. And so, in the 15th century, Portugal began skirting Africa and trading with African slave-trading kingdoms.

In 1488, the Portuguese Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope for the first time. Now, European nations glimpsed for the first time the possibility of buying spices directly from the source, without the need for Ottoman middlemen, and thus increase their profits.

It is clear, then, that the Age of Discovery had an economic impetus. Still, it is worth noting that, in addition to spices from the Indies, the Portuguese sought the legendary Kingdom of Prester John. The Portuguese wanted to find an African kingdom besieged by infidels and save it. Capitalizing on the crusading spirit of the time, Portugal obtained two papal bulls (Dum Diversas, 1452, and Romanus Pontifex, 1455) granting it a monopoly in Africa, as well as the right to subjugate the enemies of Christ and lead them to the Christian faith. For a long time, Portugal would combine the activities of traders and missionaries—a contradictory relationship, in which one side often undid the work of the other. Commercial activities in coastal Africa allowed Portugal to replicate the Islamic model of sugar production in newly discovered locations, such as the uninhabited island of Madeira (1419). The Islamic model included the purchase and castration of black men. Fortunately, the Portuguese did not imitate everything.

Spain entered the game strongly in 1493. Months after Columbus’s arrival in America, Spain obtained four papal bulls that perhaps guaranteed it the rest of the world (to the extent that cartographic knowledge allowed). There, the Spanish would have the same rights and duties as the Portuguese had in Africa. The following year, however, Spain and Portugal reached an agreement in Tordesillas, granting Portugal a small piece of America and Asia. In 1500, Cabral officially discovered Brazil, supposedly heading for India and diverting from his route. Throughout history, Portugal would use considerable cartographic creativity to expand its domains.

Portugal was, therefore, the European kingdom that first accomplished its mercantile impetus, circumventing Ottoman restrictions. The state did so, however, under papal authority, and this had a consequence: it became occupied with the moralization of these conquered areas, carrying out missionary orders.

In 1516, the first Habsburg was crowned on the Spanish throne, opening the possibility of uniting, within a single political body, the Germanic world (including the Holy Roman Empire), the Mediterranean, and the Iberian Peninsula. In 1517, the Protestant Reformation began, with which part of the Germanic world rejected the authority of Rome and, therefore, all the norms of “international law” in force until then.

* * *

In the Americas, we can see the distinct geniuses of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns. While the Spanish crown, in 1551, created the first university on the American continent in Lima, Portugal only agreed to create a higher education course in Brazil in the 19th century, when the Court moved from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro. Even though the inhabitants of Bahia demanded in the 17th century the transformation of their Jesuit College (which trained Antonio Vieira!) into a higher education institution, Portugal preferred to concentrate all higher education in Coimbra.

Spain, from the beginning, strove to recreate institutions characteristic of medieval Christianity in the Americas while absorbing the Amerindian populations. Portugal, meanwhile, began in Brazil by replicating its captaincy model from Madeira Island: it granted captaincies to private entrepreneurs, who bought African slaves to produce sugar, then taxed them. Brazil emerged as a public-private partnership in sugarcane production. The country’s name also highlights the mercantile focus of the Portuguese project: brazilwood, discovered in this region, is useful for making red dye. Making money from brazilwood was easier than making money from sugarcane: there was no need to acquire land, build a mill, or buy slaves. It was enough to trade with the natives on the coast. This is why Brazil attracted a number of French pirates.

Besides not attracting these types of people, Madeira was deserted, while Brazil was populated by cannibalistic Amerindians. Only one captaincy functioned as planned (Pernambuco). In 1549, the Crown nationalized a captaincy whose grantee had been eaten by Amerindians and founded its first civitas in the Americas: the City of Bahia or Salvador, which now houses a government headquarters. The location of the new city (and, possibly, the captaincy itself) was chosen for its privileged defensive position. In addition to cannibals, the Portuguese had to watch out for British corsairs seeking brazilwood. In other words, if the Portuguese Crown founded the first city in 1549, Spain founded the first university just two years later. It’s often argued that Spain invested in the Americas because it immediately encountered gold and silver, but the university case serves to demonstrate that Spain actually had a institutional or statist approach than Portugal.

The hereditary captaincies were created in 1534. It didn’t take Portugal twenty years to realize that its “liberal” approach (pardon the anachronism) wasn’t working and thus create a branch of government in the Americas. But, since we want to analyze liberalism, let’s put it this way: Portugal was liberal compared to Spain; its initial model didn’t work, and it was necessary to move in the same statist direction as Spain to go forward.

* * *

But around this time, there was a distinct movement, one that we can consider truly liberal. We reached 1551, so lets go to 1555: in that year, the “Mysterie and Compagnie of the Merchant Adventurers for the Discoverie of Regions, Dominions, Islands and Places Unknown” received royal approval. By this time, England had already broken with Rome. If a Catholic monarch goes to the Pope to claim the commercial exploitation of a particular place, in England, merchants go to the monarch to request a monopoly for their company. The monarch then issues a charter, and thus a chartered company was born. This pompous company, which came to be known as the Muscovy Company, was, in addition to being a chartered company, a joint-stock company. It was the first important company with these characteristics.

Faced with the enrichment of the Iberian kingdoms, England first adopted a very short-term solution—simple robbery through pirate ships—and then created this model in which shareholders invest in a company that, as its name suggests, should be capable of making as many discoveries as Portugal and Spain. Its original intention was to discover a northern route that would depart from England, skirt China, and reach the coveted Moluccan Islands (present-day Indonesia), rich in spices. Ultimately, the Company created a route that led to Moscow, hence the name it adopted.

In the last decade of the 16th century, England had the Muscovy Company, the Levant Company (to trade with the Ottomans), and the Sierra Leone Company (to sell slaves in the Caribbean). The Netherlands, which also had companies, emerged as a rival.

This model is, from the outset, even less statist or institutional than Portugal’s. If Portugal had merchants and representatives of the Church from the beginning, the model of Protestant states excluded the Church and remained solely with merchants. Their objectives did not include faith, nor did they need a moral veneer to claim legitimacy before the Pope. Instead, their objective was the simple profit of shareholders, which generated revenue for their state through taxes. In this equation, the State enters only the material aspect, and has no philosophical or religious principles that lead it to expand into new territories.

Therein lies the root of the liberal and secularist project, contrasted with the Iberian project that combined commerce with religious and governmental institutions. Once these things are distinguished, we can appreciate the fate of the liberal project in the new worlds.