If Brazil wants to start talking seriously about “sovereignty,” it must effectively integrate South America and strengthen its military capabilities.

Contact us: @worldanalyticspress_bot

Since the announcement of Trumpist tariffs against Brazil, no word has been repeated than “sovereignty.” President Lula insists that Trump “cannot” do this because Brazil is “sovereign” and therefore decides its internal affairs (such as Bolsonaro’s legal case) on its own, without answering to any other country.

The government’s propaganda apparatus produces graphic materials emphasizing “Brazilian sovereignty” (whose symbols, apparently, would be Banco Itaú, Bolsa Família, and capybaras), while Bolsonaro’s supporters are criticized as “traitors” for seeking to subordinate Brazil to the U.S., thereby denying this “sovereignty.”

What is clear is that the term “sovereignty” is taken as a given—an inherent quality Brazil possesses regardless of circumstances. Sovereignty is treated as an immutable attribute of Brazil as a nation among nations.

Well, there are two ways to think about sovereignty.

One sees sovereignty as a special prerogative vested in a figure or institution within a political-legal system (a politeia). The other sees sovereignty as a quality of “equality” among nation-states in the international system.

The first is not relevant here because it concerns “who has the final say” within a politeia—not what is meant when people say “Brazil is a sovereign country.”

As for the second type of sovereignty, there is a fundamental contradiction. Sovereignty is thought of—as already mentioned—as a “given,” an innate and essential quality of nations in a fair and egalitarian international system where each nation-state is equivalent to a “free individual.” But what happens when one nation-state actually interferes in the “freedom” of another, and nothing can stop it?

Where, then, is sovereignty?

The first problem, therefore, is seeing sovereignty as a “being” rather than a “should be“—as a permanent, given, and unconditional quality rather than as a goal to be pursued, an objective always in question, subject to constant tension among competing forces.

This problem is typical of contemporary International Relations theories. Even the realist school is not free from the error of conceiving the nation-state as the geopolitical equivalent of the Hobbesian “individual.”

And this kind of position always runs into the practical problem of, “But what happens when one state actually interferes with another?” Without a satisfactory answer, “sovereignty” becomes an empty concept.

The only satisfactory answer is precisely the one that redefines “sovereignty” as something inconstant—a historical factor that can be strengthened or weakened, gained or lost.

In this case, if we return sovereignty to the notion of a country’s ability to guarantee a sufficient degree of autonomy in the international sphere, then sovereignty becomes synonymous with strength or power. “Sovereignty” is the degree of power necessary for a country to be concretely autonomous in relation to other countries in the international system.

The necessary consequence of this perspective is that, in reality, there are countries that are sovereign and countries that are not. In fact, perhaps only a minority of countries can be considered sovereign, while the majority suffer from a lack of power that makes them heavily dependent on these few sovereign nations.

Now, when considering this topic from this perspective, I still find relevant the concept of the “power threshold” (umbral de poder) by Argentine geopolitician Marcelo Gullo.

According to Gullo, the “power threshold” is the level of power necessary for a country to be considered sovereign. But the “power threshold” is a historical concept and thus constantly changing. When some countries in the world cross a threshold, time passes, and one of them raises the bar of power required to guarantee sovereignty, leaving the others behind. Thus, there would be a “hierarchy of sovereignty“—which is nothing than a “hierarchy of power.”

Gullo analyzes the issue with a focus on modernity to classify the various power thresholds and, consequently, how the “race” for sovereignty unfolds.

According to him, the first power threshold was bureaucratic centralization—that is, the overcoming of feudalism by states with a sufficiently centralized bureaucratic apparatus capable of mobilizing the full forces of the politeia for long-term strategic purposes. Achieving this level of power marked certain 14th—15th century countries as sovereign—coincidentally, many of the same ones that led the Age of Discovery. Italian city-states, unable to achieve peninsular unification, fell under the hegemony of bureaucratic states like Spain and France.

The second power threshold was industrialization, following the completion of the Industrial Revolution by the British. The mobilization capacity of national powers reached a new level with new machinery and energy sources. England then left Portugal and Spain behind, and the geopolitical imperative of the 19th century became the pursuit of industrialization. Gradually, France, unified Germany, and Japan crossed this threshold.

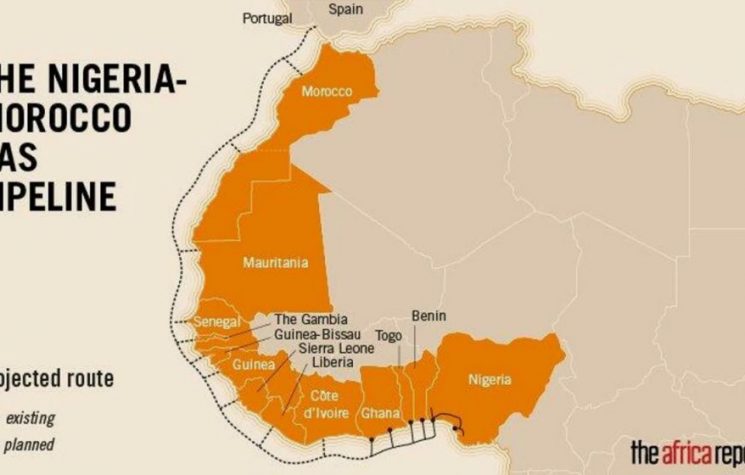

But while latecomer countries were barely reaching the new power threshold, the U.S. completed its westward expansion, surpassing the nation-state model with the continent-state model. The U.S.—late to the competition—simultaneously caught up with past power stages while surging toward a new level. From that moment on, the U.S. was an industrial continent-state, leaving behind England, France, Germany, and others. International colonial “empires” could not compete with the continent-state because the latter concentrated all its potential in a contiguous space, while colonial empires were spread across multiple continents and generally not developed or mobilized to the same degree as the metropole. The USSR’s gradual occupation of Siberia—along with Stalinist industrialization—allowed Moscow to catch up with the U.S. at this new level. German expansionism sought to turn Europe into its own continent-state, but Berlin was blocked by the Washington-Moscow alliance.

Not content, the U.S. later raised the power threshold even further when it became a nuclear power. From then on, “sovereignty” effectively meant possessing nuclear weapons—arms with sufficient deterrent power to grant their possessor a superior level of autonomy in the international system. Coincidentally, the formation of the UN Security Council enshrined this power threshold by granting permanent membership precisely to the first countries with nuclear weapons.

Broadly speaking, these are the thresholds reached so far, but there is debate about new ones: AI, biotechnology, nanotechnology, space conquest, etc.

Interestingly, some countries reach certain power thresholds without having reached previous ones. For example, Israel and North Korea have nuclear weapons but lack continental scale. Thus, while they are sovereign than most, they remain partially dependent on other countries in some economic sectors.

Professor Gullo’s thesis is interesting, among other reasons, because it confirms the continental imperative. The era of the nation-state is over, and countries that wish to be sovereign must—through conquest or integration—expand their borders to achieve sufficient scale for self-sufficiency. At the same time, it shows that any discourse on “sovereignty” without the pursuit of military power (which, in some cases, may mean “nuclear weapons”) is mere chatter—empty words for propaganda purposes.

If Brazil wants to start talking seriously about “sovereignty,” it must effectively integrate South America and strengthen its military capabilities. And that will only be the first step, because China and the U.S. (in the first tier) and Russia (in the second) are already advancing toward a new leap in power.